“I will go from this place to my home.”

When I had said this the deeper voice of an older man answered:

“And since I am going to that same place, let us journey there together.”

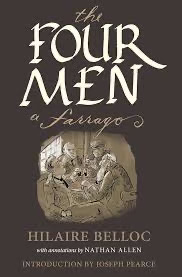

The opening of Belloc’s The Four Men quickly introduces us to two needs: the need to journey home and the need for companions along the way. At the beginning of the text, Hilaire Belloc positions his autobiographical self in a rather enviable setting- at an old English Inn called the George, with a pint of porter in hand and sitting by the fire sometime in late October. And yet, his character is restless. Not able to perceive any value in his current mode of earning and spending hither and thither, his mind begins to feel a mighty magnet pulling him homeward to Sussex. “Consider how many years it is since you saw your home, and for how short a time, perhaps, its perfection will remain,” he says to himself, and with a slap of hand on the table, resolves to begin the journey.

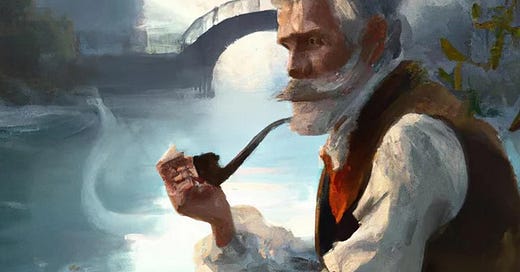

An old man with “Iris eyes…deep set in his head…full of travel and sadness” and with “a strong, full beard, as grey and stiff as the hair of his head,” reveals that Belloc’s pondering was not made in solitude, and pledges his company to journey, which Belloc accepts, because “all companionship is good, but chance companionship is the best of all.”

For all the story, songs, deep reflections, hardships and joys they share along the three day autumn journey the proper name of each is kept hidden. Belloc dubs himself “Myself,” and the old man is given the scratchy name of “Grizzlebeard.” Later on, two other men join them in quick succession: “Poet,” and “Sailor.” I have to admit that Grizzlebeard is my favorite, though the characters interweave so much in the narrative of The Four Men that it is hard to tell them apart. Perhaps it is because Grizzlebeard has the added advantage over the others of aged wisdom, of travel-worn experience. There are many Grizzlebeards I have come across in literature who I would not mind sharing a pint with, including Gandalf, Tom Bombadil, Merlin Treebeard, Mr. Badger, and Puddleglum. There is a quirky, sometimes cantankerous mischief about them, as if they hold a secret lightly, and are just waiting to be asked. They are full of story and myth, and deeply, deeply rooted. They are focal points of re-enchanting the world.

In his erudite book on Belloc No Alienated Man, Frederick Wilhelmsen posits that these four men are actually the four facets of Belloc himself, and each of these work towards an integration of Belloc’s soul and being, an integration largely lost in modern man. This integration allows Belloc to revel both in the solid reality of Earth and the solid reality of the Heaven. Not only, Belloc of course: This is Holy Order for all. Divine Reality, which has been tasted for millennia before our current modernist plight, and desperately needed once more, was relational: Earth and Heaven spoke to the other, with Man at home in each, at the good Lord’s open and merciful invitation.

The curse of Modern Man, according to both Belloc and Wilhelmsen, was a disintegration of man’s relationship with the Earthly and Divine. No more of Man’s hands encrusted with the dirt of the earth after gathering harvest from the land, sitting down to pint and pipe in the evening hours and sighing at the sight of a cathedral of constellations. Instead, as Wilhelmsen says:

Human unity was gradually lost, and a new man came into being. This man has his life neither in the rooted things of the world nor in a heaven beyond. Nor is he Christian Man, man reconciled to himself. This new man looks neither outward and above nor outward and round about him. He looks within, and attempts to find his salvation by a penetration and purgation of the hidden depths of his own personality. This is Modern Man, man twice alienated from himself, and he has not yet found his soul.

Modern Man is the alienated self disconnected from the world, the heavens, others, and himself. Modern Man asks, as TS Eliot questioned in “The Love Song of J Alfred Prufrock:” “Do I dare disturb the universe?” The isolation which comes with technology, a culture of consumerism where things are reduced to use and production, and the loss of any spiritual center further ingrain this self-imposed alienation. This is the plight of Modern Man. In some prevailing philosophies, Grizzlebeard is dead, the Poet is silent, the Sailor washed ashore, and Myself grapples not with loneliness, but Void.

Watch the reaction to these statements, for it reveals the person who has heard it. Modern Man sits down with a long sigh of despair, and his chin will rest on his chest in resignation. “Yep, you’re right,” he will concede, before slipping back into a scrolling stream of content online.

A Grizzlebeard will stand up, pierce his eyes towards the horizon, take a long swig of a properly fermented beverage, locate the nearest forest, and loudly tramp off into its interior, nonsense verse rattled off in a cheery baritone or reedy tenor, and the most holy of middle fingers raised to the Void and Despair from which he has turned his back.

He will be a story-teller.

He will sing songs.

He will recite poetry.

He will feel rain.

He will circle firelight.

He will tromp miles of wooded paths.

He will smell of earth and leaves and sweat.

He will chop, mince, dice, plant, shape, drink, desire, and dive.

He will worship.

His will be a holy farrago of existence.

And, my friends, he exists.

We are at a point in our cultural milieu where the modern and postmodern just can’t offer any more of what is needed to fulfill soul and spirit. We need a home to go to, and companions along the way.

I’m happy to report that over the years, looking up from the page of Grizzlebeards who I know and love and still cherish in my reading, there are flesh-and-blood Grizzlebeards all around us. Full of story, song, poetry,

I mention just a few: Malcolm Guite, Martin Shaw, John Moriarty, Casey B. Head, C.R. Wiley, Ryan B. Anderson, Anthony Esolen.

They are out there. Some are on Substack. Go read them.

I’m looking forward to exploring them further in my writing here at Pyne, Pipe, and Cross.

There’s hope for us, Modern Man. It’s time to go home.

Grizzlebearded. Love it. This piece is pungent with the deep earth and trailing stardust that many of us long for. Now I must pick up those books!

Ah me! Soul-satisfying to read. Enchanting. Every time I read this (yes, I keep coming back) I forward it to someone else...those who have lifted their chins off their chests, stood up, and followed the bird song and thunderous water. Thank you for lighting the way!